-40%

COTTON GIN TRIP Framed OIL PAINTING on CANVAS by CARMEN CUMMINGS BLACK AMERICANA

$ 79.2

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

COTTON GIN TRIP Framed OIL PAINTING on CANVAS by CARMEN CUMMINGS BLACK AMERICANA///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

THIS MONTH, WE ARE PLEASED TO OFFER MANY FINE ANTIQUE AND COLLECTIBLE ARTIFACTS AND RARITIES FROM MISSISSIPPI AND LOUISIANA ESTATES AND PRIVATE COLLECTIONS

PLEASE

CHECK

OUR

OTHER

EBAY

LISTINGS

FOR

MORE

EXAMPLES

OF

EARLY

ANTIQUES

&

COLLECTIBLES

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

DESCRIPTION

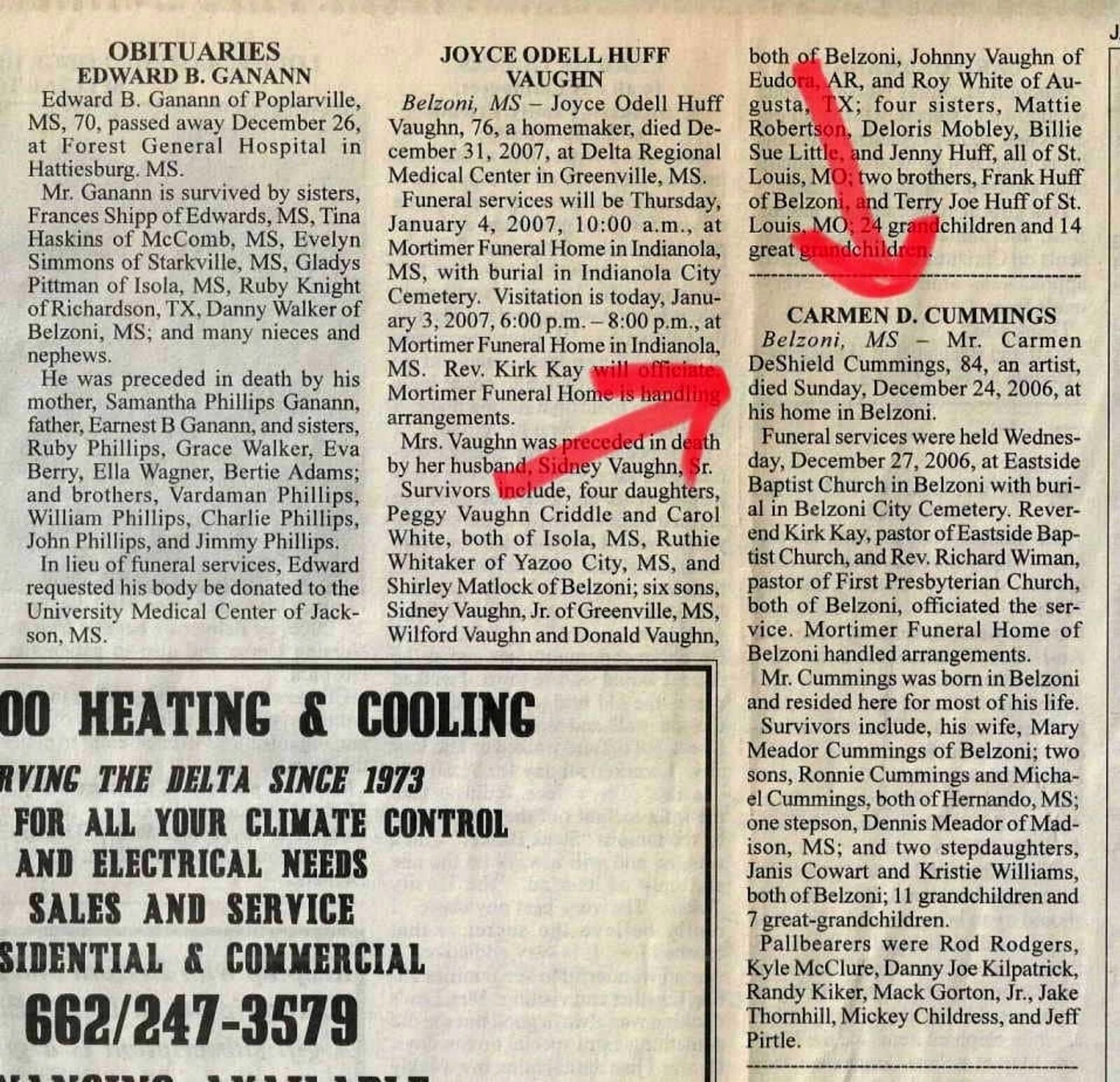

FROM AN OLD AND PROMINENT MISSISSIPPI ESTATE, A UNIQUE OIL PAINTING ON CANVAS PANEL BY ARTIST CARMEN DeSHIELD CUMMINGS, A LIFE-LONG RESIDENT OF BELZONI, MISSISSIPPI, WHO DIED AT HIS HOME IN IN 2006 AT THE AGE OF 84.

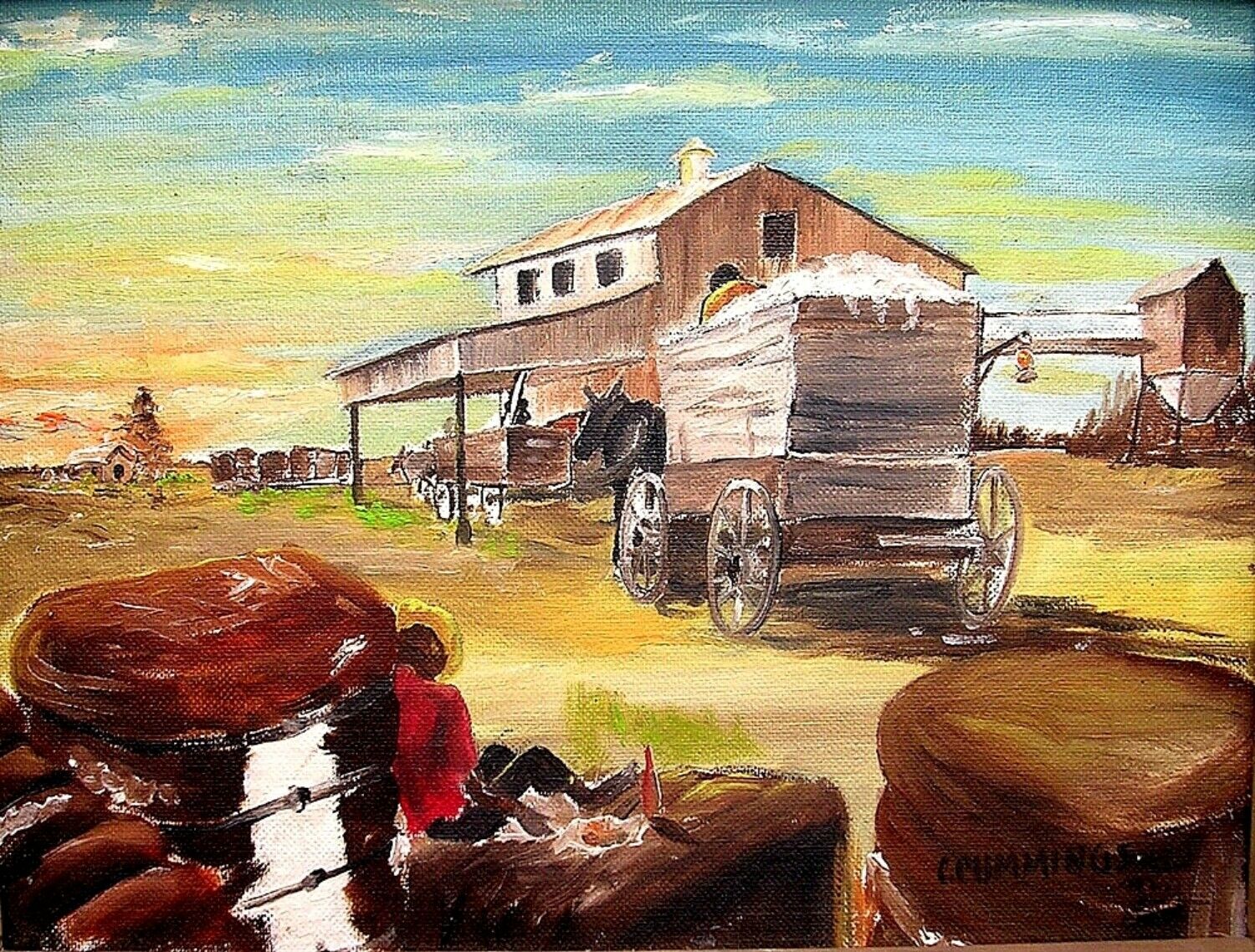

THE 9 x 12" CANVAS IS PRESENTED IN A COMPLIMENTING NATURAL WOOD FRAME OF DEEP MOULDING, MEASURING 14.5 x 12" OVERALL.

THE IMAGE DEPICTS HORSE DRAWN LOADED COTTON WAGONS LINED UP FOR UNLOADING AT A COTTON GIN. TO THE FOREGROUND, A AFRICAN AMERICAN MALE NAPS ALONGSIDE BALES OF COTTON.

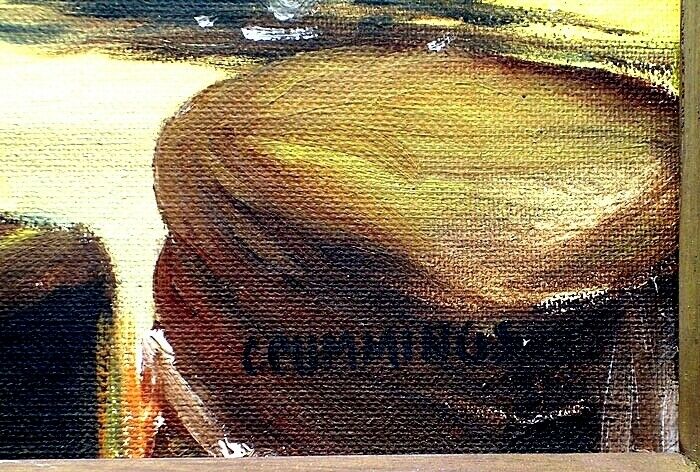

THE SIGNATURE OF THE ARTIST IS FOUND TO THE LOWER RIGHT CORNER, READING ~

CUMMINGS

CONDITION REPORT

> A NOTABLY WELL PRESERVED EXAMPLE ~ OVERALL FINE, VINTAGE CONDITION, BEST NOTED BY EXAMINING THE IMAGES OFFERED.

COTTON FARMING IN MISSISSIPPI ~ WRITTEN by J. TOBY GRAVES, COPIAH-LINCOLN COMMUNITY COLLEGE for the MISSISSIPPI ENCYCLOPEDIA

Cotton was first grown in what is now Mississippi in 1795 in the Spanish-ruled Natchez District as an alternative to tobacco and indigo. Cotton cultivation in the Mississippi Valley previously had been either unsuccessful or unproductive. Despite Eli Whitneys inventing the modern cotton gin in 1794, cotton remained a marginal crop in the early 1800s, largely because the strains initially used-Creole seed and then Tennessee green seed-provided only mediocre yields. Mississippi growers began using the more productive Mexican seed around 1820, and within a decade Dr. Rush Nutt had developed Petit Gulf cotton, a Mexican-Tennessee green hybrid, on his Rodney plantation. This seed produced the white gold that helped to make Mississippi the nations top cotton-producing state.

With the high profitability of cotton during the antebellum period came enormous population growth in Mississippi.

During the antebellum period cotton production spread east from the river valleys along Mississippis western border. Cotton became a primary endeavor of settlers throughout the state except along the coast. While regions such as the Pine Belt quickly proved unfavorable for cotton cultivation, the crops profitability encouraged settlers to try. The Delta was the last region of the state populated by whites and enslaved blacks, as its impenetrable thickets and canebrakes hindered widespread settlement until after the Civil War. Ironically, however, it proved to be some of the worlds most productive cotton land.

The Civil War devastated Mississippis cotton growers. Many farms and plantations lay in physical ruin, and the loss of the labor force was even more overwhelming. Without cheap labor, wide-scale cotton cultivation was impossible.

This issue was resolved with the development of the sharecropping system. Poor whites soon began to find themselves in much the same situation when debts resulted in the loss of their small farms. Sharecropping further increased Mississippis economic dependence on cotton agriculture. Landlords often demanded that sharecroppers grow almost nothing except cotton.

During the first decade of the twentieth century Mississippis cotton growers faced a new and potentially devastating problem-the boll weevil. Mississippi agricultural scientists made preemptive efforts to attempt to curtail boll weevil infestation. The Delta Branch Experiment Station was established at Stoneville in Washington County for the sole purpose of developing a way to stop the weevil. The experiment station was run by the Mississippi Agricultural Extension Service, one of the most visible creations of the progressive era in rural Mississippi.

During World War I Mississippi cotton growers experienced a boom in international demand as well as prices. Farmers sought to grow as much cotton as possible. With the end of the war, however, cotton prices dropped precipitously and did not increase significantly until 1933. In spite of the poor market and mounting debts, Mississippi farmers continued to focus on growing cotton. By the end of the 1920s, the states cotton economy was on the brink of collapse. Nevertheless, the highest recorded acreage planted to cotton was in 1930, at 4.163 million acres.

Pres. Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933 and immediately acted to remedy the agricultural crisis. His most significant move was the creation of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, which stabilized prices by paying farmers not to grow cotton. However, the program also resulted in the eviction of thousands of sharecroppers because landowners had no need for laborers to work fields that were not planted.

The changes in cotton production that developed out of the Great Depression and New Deal accelerated during World War II. The war brought tremendous demands for virtually all products, including cotton. Many former sharecroppers and agricultural laborers left Mississippi and sought employment in northern factories. At the same time, cotton was in high demand. This dichotomy resulted in perhaps the greatest advancement in cotton agricultural technology since Whitneys cotton gin: the first effective mechanical cotton picker, developed by International Harvester in 1947. Within two decades virtually all of Mississippis cotton sharecroppers were gone.

During the second half of the twentieth century many Mississippi planters and farmers moved away from cotton production and toward other row crops such as soybeans and corn as well as highly commercialized catfish and poultry operations. Cotton has recently ranked third, behind poultry and forestry, among Mississippis leading forms of agriculture. Today, approximately 1.1 million acres are planted to cotton in Mississippi, depending on a number of factors, including weather, price, and commodity markets.

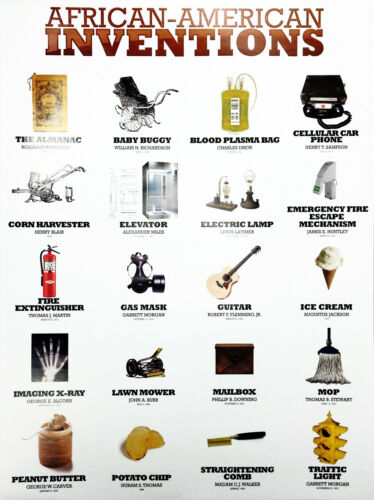

COLLECTING AFRICAN AMERICAN MEMORABILIA

For the last quarter-century, those interested in African American history have flocked to one of the long-neglected areas of American collectibles: African Americana, also known as black memorabilia. A daguerreotype of abolitionist Frederick Douglass; notable diplomas from the early history of black universities; a rare rifle carried by a black Civil War soldier; a quilt sewn by African American grandmothers: these are just some of the objects that institutional collectors and individuals, both black and white, currently are seeking out.

Black memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and ephemera relating to African American and Afro-European history. Most of this material was produced from the 18th through the 20th centuries. Frequently, these household items reflect racist ideas about black people through offensive and dehumanizing caricatures. However, black memorabilia also encompasses objects with positive connotations, commemorating civil rights advances or achievements by scholars, artists, musicians, athletes, politicians, and other members of the black community.

Some of the earliest items associated with black memorabilia were actually produced in Europe. These ornamental portrayals of Africans, referred to as blackamoors or blackamores, appeared on enameled jewelry, pottery, sculptures, and other decorative arts beginning as early as the 13th century, when black servants came to represent the pinnacle of wealth.

Displaying a blend of stereotypical Oriental, Arabian, and African attributes, blackamoor objects typically feature a head or bust with dark skin, a colorful turban, and elaborate gold jewelry. The trend for these exoticized pieces peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as European countries increasingly colonized and traded with areas in Northern Africa.

Across the Atlantic, as became entrenched in the American way of life, representations of African Americans helped to reinforce this inhumane system. Just as white superiority was cultivated by clergymen, politicians, and scientists, this belief system was also spread through popular culture, via theatrical performances, song lyrics, advertising imagery, and the design of household objects. After the Civil War and the end of Radical Reconstruction in the South, Jim Crow laws and public lynchings became means of subjugating black Americans. At the same time, advances in printing and manufacturing technology allowed companies to churn out products with popular caricatures of black people.

Much of this racist imagery perpetuated the association between African Americans and household servitude, like the smiling cook used in Cream of Wheat ads. Others aimed to get a laugh with depictions of simple-minded oafs obsessing over watermelon or being attacked by alligators. Caricatures of black people appeared on every imaginable product, although skin color was used especially often as an advertising punchline for goods like ink, tooth paste, shoe polish, washing powder, and house paint.

While this packaging documented existing opinions about African Americans, it also influenced cultural norms moving forward: Even as progressive groups questioned the ethics of racial prejudices, popular depictions of black Americans as subhuman often undermined their efforts. Sheet music for vaudeville tunes known as coon songs-which described black men as uppity, shiftless, razor-wielding, drunken, gambling, and lecherous fools-were also wildly popular at the turn of the century.

During the 19th century, several offensive stereotypes became commonplace, including male savages or brutes, subservient Toms and mammies, sexualized Jezebels, pickaninny children, and ignorant coons. Most of these featured the same physical traits-very dark skin, oversize red lips, and bulging eyeballs.

Eventually, familiar characters like Golliwog, Aunt Jemima, and Little Black Sambo were created as amalgamations of various racial stereotypes to market all manner of toys and household products. Dressed in a bright blue jacket with a red bow tie and trousers, Golliwog (or Golliwogg) was originally a character in Florence Kate Uptons book The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls, published in 1895. The Golliwog doll in Uptons story was modeled after minstrel performers, who were known for their ugly blackface representations of African Americans. After Uptons book series became a success, Golliwogs became especially popular as rag dolls, though the character was also featured on products like postcards, clocks, pottery, and wallpaper.

At the time, the dominant representation of black children was as pickaninny kids, who were dirty, unkempt, and barely clothed-almost animal in their wildness. These portrayals were seared into the collective imagination with the 1922 arrival of Our Gang, the film series that would eventually become The Little Rascals. Characters like the infamous Buckwheat epitomized the bumbling, poorly dressed pickaninny.

Perhaps the most popular version of the pickaninny caricature was introduced with Helen Bannermans 1899 book, Little Black Sambo. This childrens story follows a young black boy as he outwits a series of tigers, and is finally rewarded with tiger-striped pancakes. Though the tale itself was not inherently racist, the name Sambo was a common epithet for a lazy servant, and the books illustrations reinforced a variety of negative stereotypes about black people. Additionally, the immediate popularity of Little Black Sambo resulted in a proliferation of knock-off versions, many of them incorporating more offensive storylines and imagery.

Though Aunt Jemima is most famously associated with the Quaker Oats pancake mix, her character was originally based on a minstrel song from 1875 called Old Aunt Jemima. In her apron and polka-dotted kerchief, Aunt Jemima became the familiar face of the mammy stereotype, a motherly and overweight black woman who is visibly happy in her subservient position. The mammy caricature is one of the most enduring black stereotypes, and was often used as proof that servitude was a mutually beneficial arrangement. Mammy caricatures appeared on a wide variety of household objects, especially kitchen-related items like cookie jars, dish towels, pitchers, string holders, salt and pepper shakers, tea tins, and detergent boxes.

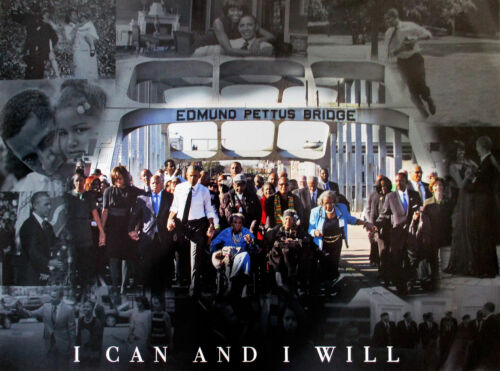

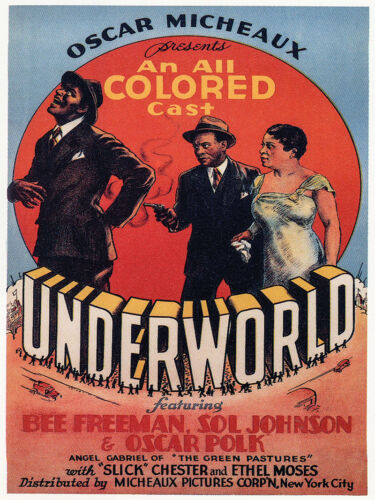

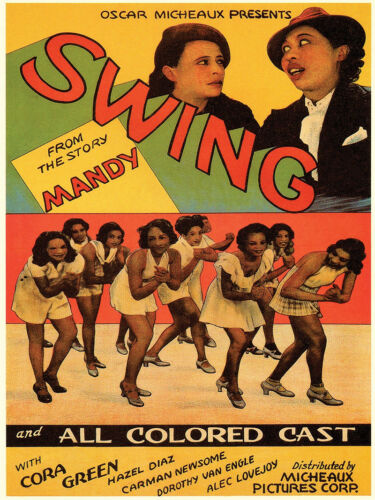

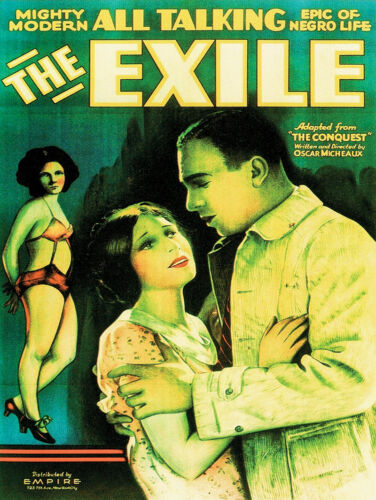

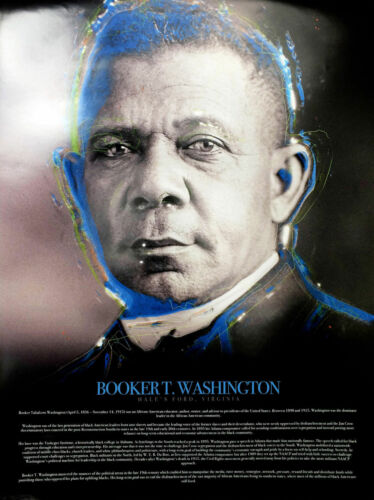

In the face of such negative portrayals, African Americans pushed for change, creating their own representations and making strides towards greater equality in the public sphere. Some of the most coveted items of Black Americana are connected to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, like comic books that captured the story of Dr. Martin Luther King or newspaper clippings covering Rosa Parkss trial. Political icons ranging from Frederick Douglas to Malcolm X have been commemorated with collectible objects like silver spoons, decorative plates, and ceramic figurines.

Memorabilia connected with all types of black celebrities is highly valued, from tickets for Josephine Baker performances to signed photographs of Muhammad Ali, original Duke Ellington records, and Jackie Robinson baseball cards. Other names are less recognizable to modern ears, but represent equally important milestones for black Americans, such as Madam C. J. Walker, whose popular hair tonic made her one of Americas first female millionaires.

Products targeted toward African American consumers make up another important segment of Black Americana, like Walkers Wonderful Hair Grower or early issues of groundbreaking publications like Ebony and Jet. Original Patty-Jo dolls also fall into this category: Launched by the Terri Lee doll company in 1947, Patty-Jo was created explicitly for black children by African American illustrator Jackie Ormes.

Even some offensive objects of Black Americana celebrate the successes of African Americans. For example, black jockey figurines, common to white suburban communities during the mid-20th century, arent only a reminder of black servitude. Rumor has it that George Washington commissioned the first statue of a black jockey holding a lantern after his black groomsman, Tom Graves, who froze to death while lighting the way for revolutionary troops crossing the Delaware River. In fact, black jockeys were some of Americas first sports stars, as represented their masters teams in southern races beginning as early as mid-1600s. A black jockey named Oliver Lewis won the first-ever Kentucky Derby in 1875, and African American athletes dominated the sport well into the 20th century.

Today, historic artifacts connected to are among the most desirable pieces of Black Americana, which include trade documents, shackles, and identification tags, as well as abolitionist circulars and books. Other signs of institutionalized racism, like signs from the Jim Crow era designating separate spaces for colored and white, are also sought by collectors.

In many ways, modern attempts to achieve a more equitable society have served to whitewash over these painful realities. Few realize that Agatha Christies best-selling mystery novel of 1939, And Then There Were None, was originally titled Ten Little --- , after a popular nursery rhyme that recounts the deaths of ten black children (the poem is called Ten Little Indians in the American text).

While many fear the preservation of Black Americana serves to prolong racist prejudices, others collect these objects to ensure that Americas troubled past isnt forgotten by future generations. In the words of David Pilgrim, founder of the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Michigan, Use items of intolerance to teach tolerance.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

PLEASE USE THE EBAY "

CONTACT SELLER

" FUNCTION TO CONTACT US AND RESOLVE ANY QUESTIONS BEFORE BIDDING

FREE SHIPPING ON THIS ITEM TO DOMESTIC ADDRESSES ONLY

INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING AVAILABLE FOR SOME ITEMS ~ CONTACT US FOR A RATE QUOTE BEFORE BIDDING

<<<<<

WE NEVER CHARGE A HANDLING FEE & ALWAYS OFFER COMBINED SHIPPING

>>>>>